“While electric light has for some years been without rival in respect to its cleanliness, convenience and safety from fire risk, it has suffered from one important drawback which has limited its adoption in country houses – the necessity of a supply of electricity to the premises”. A special supplement to Country Life magazine went on to advise the owners of grand estates how they might install generating plants to bring the latest comforts of modern life to their country house.

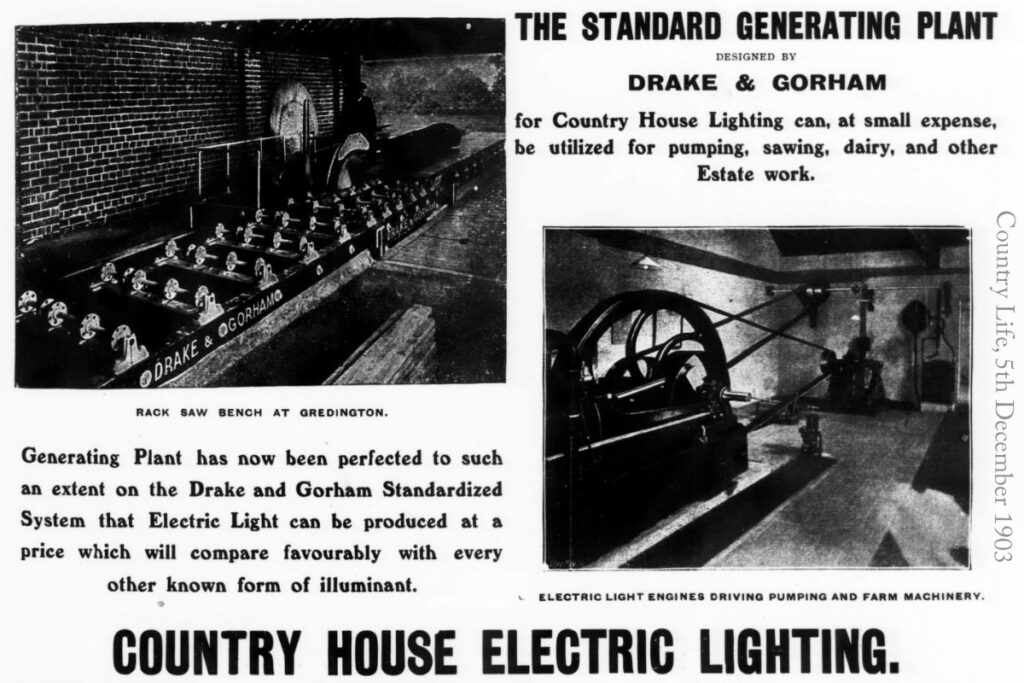

Installation of simple electrical lighting and generating plant became a practical, if costly, possibility by the early-1890’s, but was still a novelty in 1900 when Sir Edward and Lady Colebrooke chose to install electric lighting in the extravagant new country house they were building at Glengonnar near Abington. The electrical work was overseen and installed by the firm of Drake & Gorham who specialised in county house systems and had a base in Glasgow. The company installed electric lighting to Buckingham Palace soon after the death of Queen Victoria, (who had a distrust of electricity.)

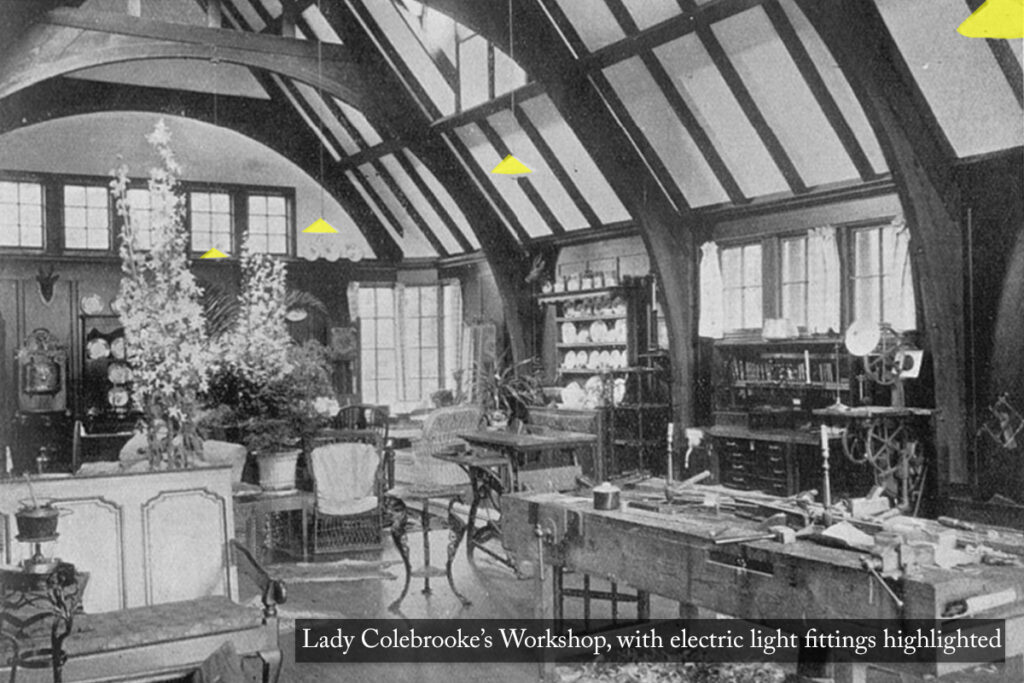

We know no details of the installation at Glengonnar House, but there must have been a significant power demand to light over 50 rooms, run woodworking machinery in Lady Colebrooke’s workshop, and probably power other novelties such as servant bells and indicators.

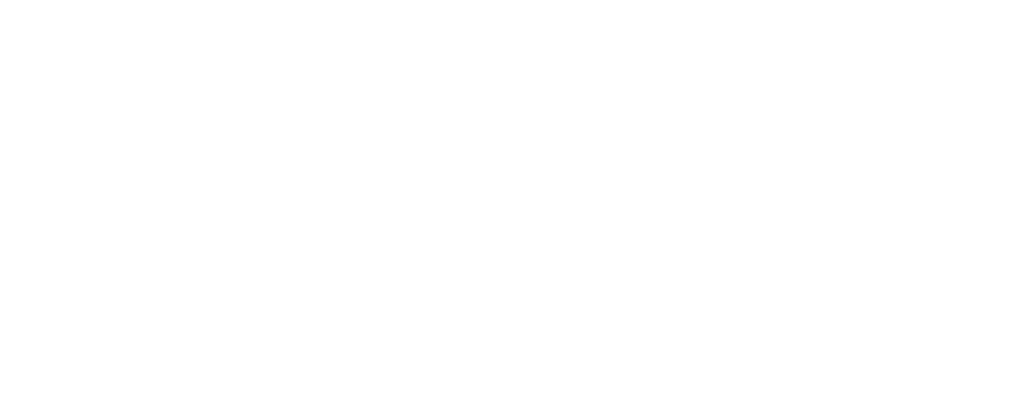

At that time, typical generating plant used to serve country houses was powered by an oil engine driving a dynamo by means of a belt. Direct current was generated at a low voltage (often about 50V) which was stored in large banks of lead-acid batteries and drawn off as required. With this arrangement the engine was run intermittently to recharge the batteries as they became exhausted requiring regular supervision and adjustment. Country Life magazine offered reassurance that these electrical duties could easily be carried out by a chauffeur as he was “already skilled at starting engines”. Alternatively, it was suggested, such duties might be undertaken by a gardener.

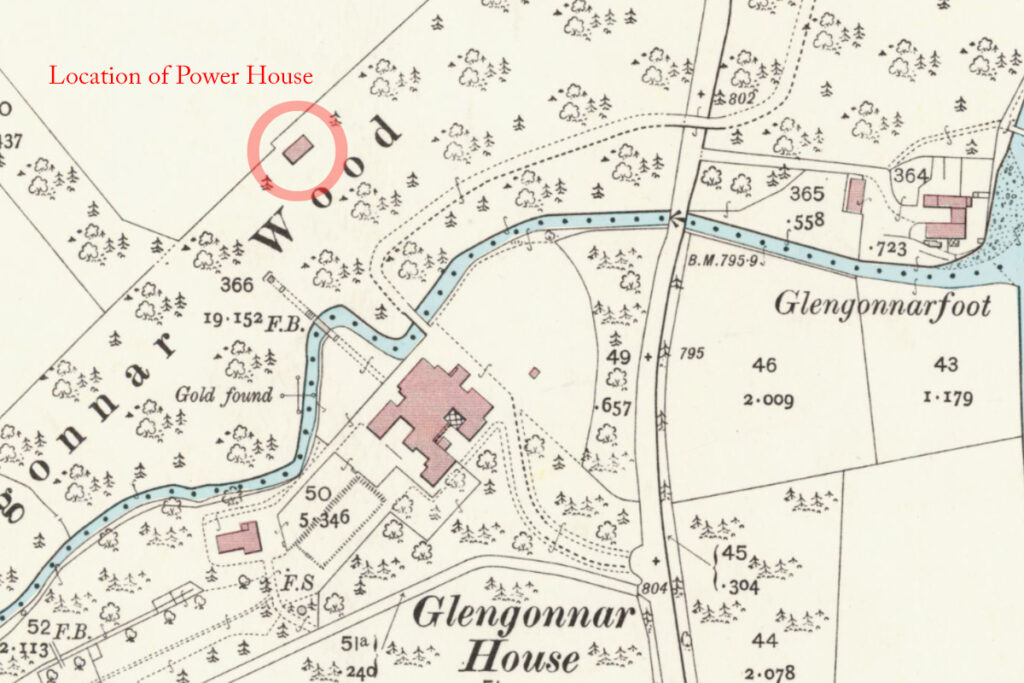

The ruins of a substantial brick building survives on the edge of Glengonnar wood on the north side of the burn and located at suitable distance from the country house to be out of sight and out of earshot. It is some distance from a road, but a kink in the fence line suggested that fuel and other supplies might have been brought across the adjoining field. The plain structure is constructed from robust Cleghorn terracotta bricks. The building has a stout brick dividing wall, presumably separating the engine, generator and switchgear from the space filled with long banks of batteries. Although no trace of the roof remains, it might be imagined that the space above the battery area would have been well ventilated with a louvres

It seems unlikely that Glengonnar House would have been re-wired and connected to the public electricity supply when this became available after the first world war, therefore the little power station might have remained serviceable until Glengonnar house was abandoned in the 1930’s or 40’s.

The electrical contractors, Drake & Gorham later diversified their activities but lost their identity following a sequence of mergers; however a former overseas subsidiary now trades as Drake & Gorham, and are Zambia’s leading air conditioning company.

Robin Chesters, 28th January 2025

Unless otherwise stated, all text, images, and other media content are protected under copyright. If you wish to share any content featured on Clydesdale's Heritage, please get in touch to request permission.