Climb over the field gate, venture through the long and rather intimidating concrete tunnel beneath the M74, and you emerge into the lovely wooden glen of the Glengonnar burn. Few people come here now; and the only footprints you’re likely to find are those of the deer who graze undisturbed among the trees. Amongst the shrub and brambles, an old stone bridge still spans the burn, and within the woods you may come across a series of low walls and banks that mark out the changing levels of the land. These were once the terraces of a fine garden, while an area of flat ground close to the M74 marks the site of Glengonnar House; an extravagant Edwardian mansion that once boasted 37 bedrooms.

Glengonnar House, initially known as Glengonnar Lodge, was remarkable in many respects, The eccentric cottage-style country house seems to have been especially designed to impress, entertain and reflect the impeccable tastes of its owners. Glengonnar was the scene of many fashionable parties and welcomed many prominent house guests; the most notable being King Edward VII. However Glengonnar was also remarkable in being regularly occupied for little more than twenty years. The reasons for such a short life are far from certain, but seem likely to reflect the glamorous lives and changing fortunes of its owners, Sir Edward and Lady Colebrooke.

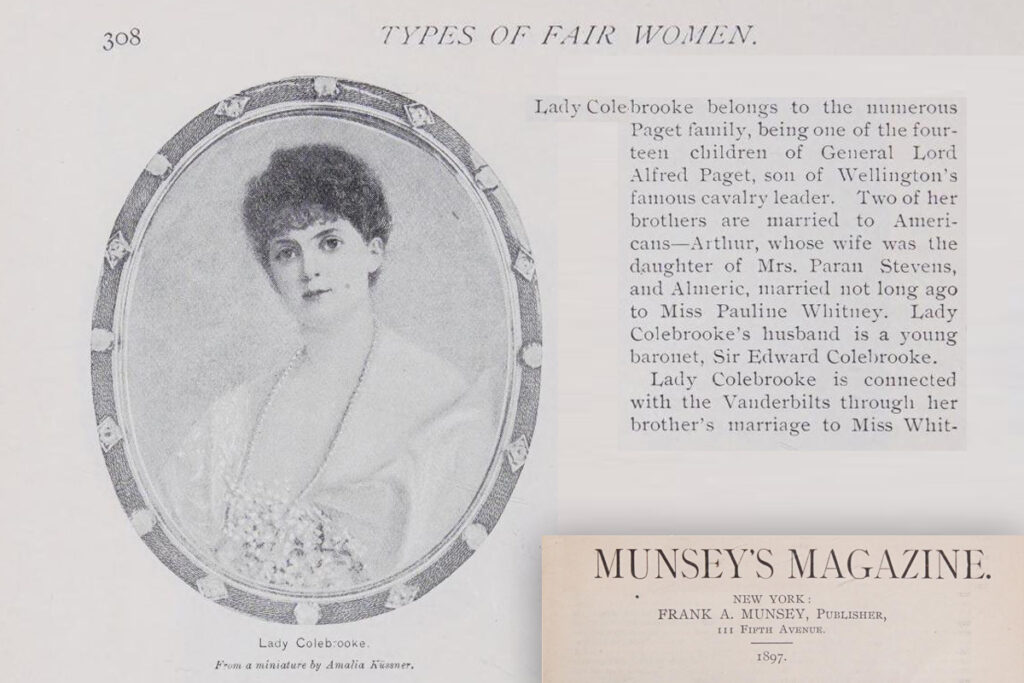

On 17th June 1889 Sir Edward Colebrooke married Miss Alexandria Paget at St Peter’s Church in London. The 400 guests at this fashionable society wedding included the bride’ s godparents; the Prince and Princess of Wales. Alexandria was daughter of a famous and respected liberal politician and was the 13th of 14th children. Edward was the oldest son of the local MP and Lord Lieutenant of Lanarkshire, and was heir to an estate that extended over 30,000 acres of South Lanarkshire, which included the villages of Abington, Crawfordjohn, and much of Crawford. On their wedding day, Edward was 28 and Alexandria 26 years old.

Edward succeeded to the baronetcy in 1890 following the death of his father. The couple spent little time on the estate at Abington House, preferring a fashionable life at the heart of London society.

Their daughters Mary and Bridget were born at their London town house in 1890 and 1892, however Guy, their only son and heir, was born in Abington during 1894, sparking great celebration in the village. Edward served the royal household in a succession of roles, but seems to have had little interest in wider politics. It was said that it was “probably due to his retiring disposition that he has not figured so prominently in public as he might have done”.

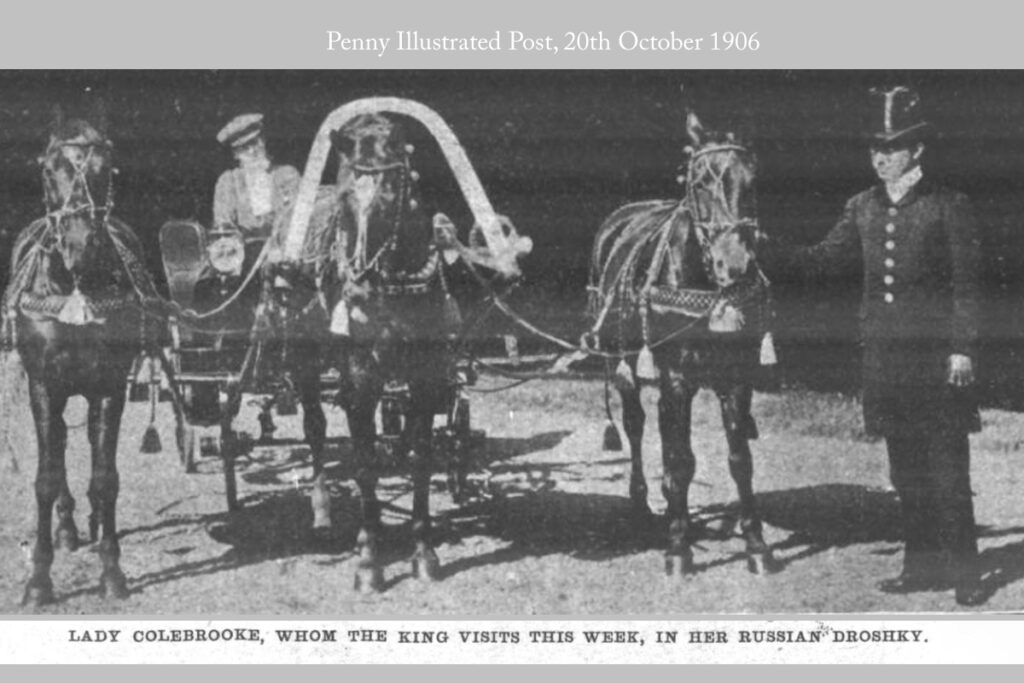

In contrast, Lady Colebrooke was a leading light in London society, variously described as “like a jewel, always sparkling”, “a beautiful woman with dark hair, blue eyes and brilliant colouring”, “a charmingly vivacious little personage”. However she was far more than just a society belle, and it was said that “there are few who are more active in the discharge of their social duties or more conversant with the whole duty of the society leader”, Travelled, ambitious and a consummate hostess, she wielded substantial social influence and political power. The press also delighted in her many other interests that often defied the conventions of the day. She was a fine “whip” who sometimes drove a three-horse carriage, an accomplished carpenter who built her own furniture, and a gifted carver and sculptor. With such strength of character it might be imagined that Lady Colebrooke; described as “a beauty, a wit and an artist”, would take the reins when drawing up plans to redevelop the Colebrooke’s Scottish estate.

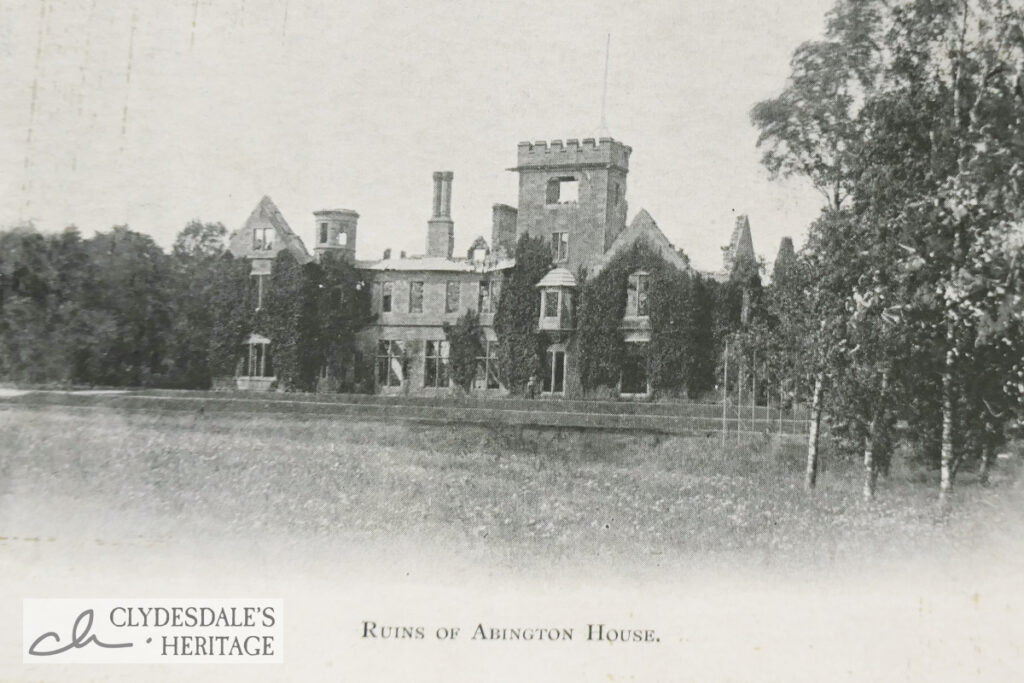

Abington House – the main country seat of the Colebrookes – was a substantial residence that had been extended and improved through the years, and as recently as 1884 had been substantially remodelled by noted architects Dick, Peddie & McKay. In October 1898 a fire broke out on the top floor of the house and gradually progressed through the rest of the building, giving time for most furniture and possessions to be saved. The damage was estimated to be £30,000, most of which was covered by insurance.

The decision not to repair Abington House, but instead to build a new house on a new site, must have been taken very soon after the fire; perhaps a new house in the glen was something that had already been considered. Most design and planning work for Glengonnar House must have taken place during the course of 1899, and a practical start was made on construction before the turn of the century, most presumably funded by the insurance payout. By odd coincidence, two fires broke out at the Colebrooke’s smart London properties within six months of the Abington fire.

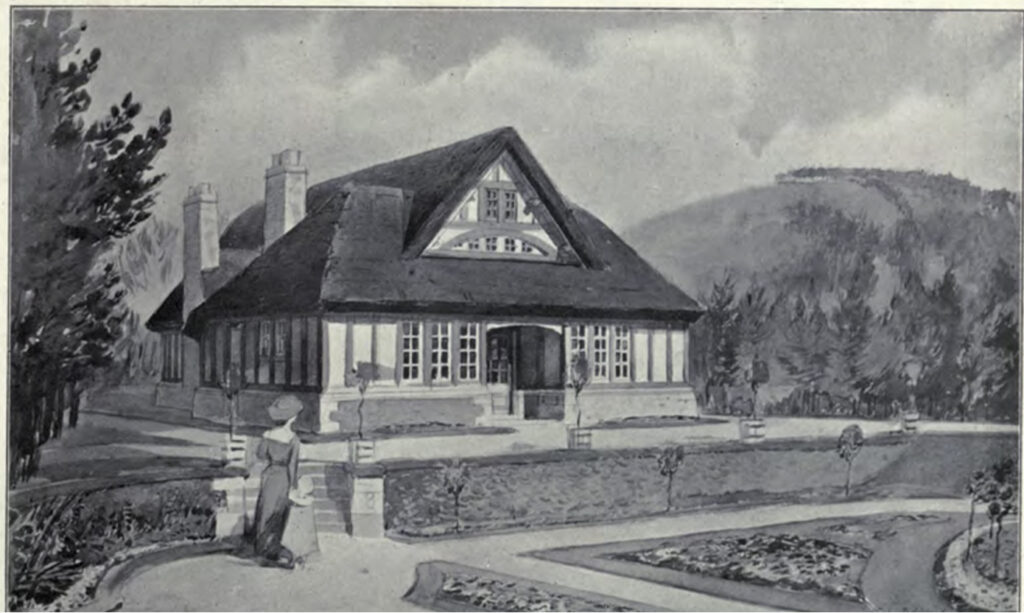

Glengonnar House was built within the picturesque wooded glen of Glengonnar burn. An old mill building was cleared to make way for the new house, although the road that served it was retained, Lanark-based architects Traill and Stewart designed a substantial mansion; their only other notable commission was for the Lindsay Institute in Lanark – now the public library. One commentator described Glengonnar as “built in the cottage style of architecture and with its red and grey stone capped with similarly coloured tiles and slates, presents a striking and picturesque appearance, the quaint effect being enhanced by the innumerable short red chimney cans.” Another described it as “a unique country house that gives expression to many novel ideas and theories in house construction”.

The rambling design of the mansion incorporated architectural elements and finishes that were greatly fashionable at the time, but perhaps the overall arrangement lacked the simplicity and balance of the finest houses built in the arts and crafts style. The house won no awards. The irregular shape and roofline of the building gave the impression of a house that had been added to over an extended time. It seems to have been completed in phases. The Colebrookes were entertaining at “Glengonnar Lodge” by 1902, and further building works seems to have been completed by about 1904. A final wing was completed in advance of the King’s visit in 1906, providing accomodation for the Royal household that was completely independent of the rest of the house. The decoration of the interior of the house featured much carved woodwork, doubtless reflecting Lady Colebrooke’s taste; and perhaps her own handiwork. The house, nestled within the picturesque wooded glen, was set within extensive lawns, terraces, gardens and shrubberies.

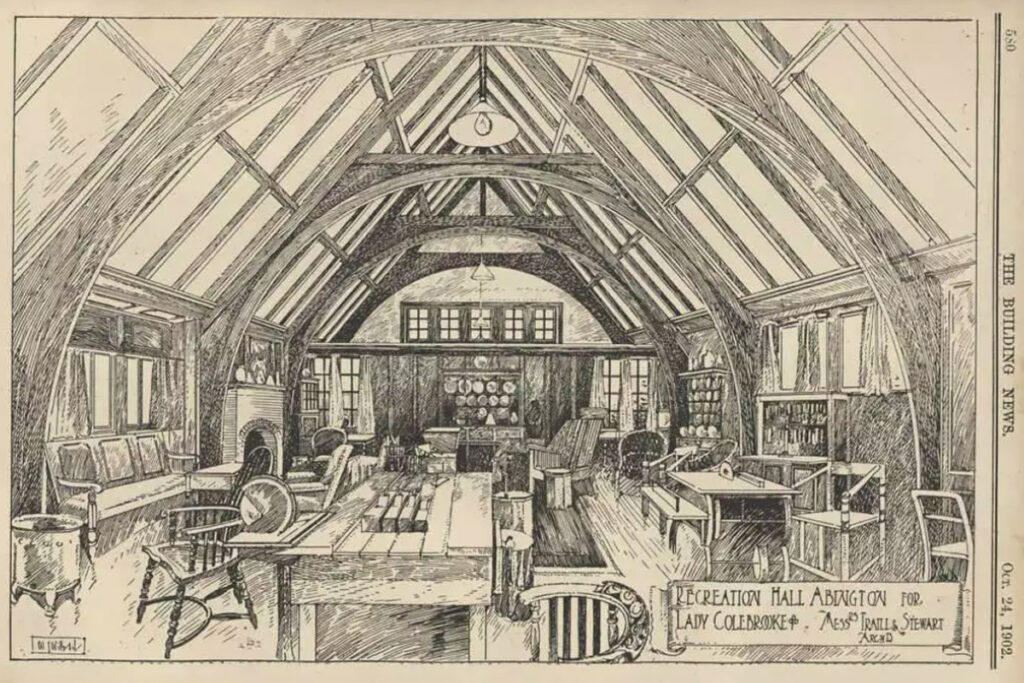

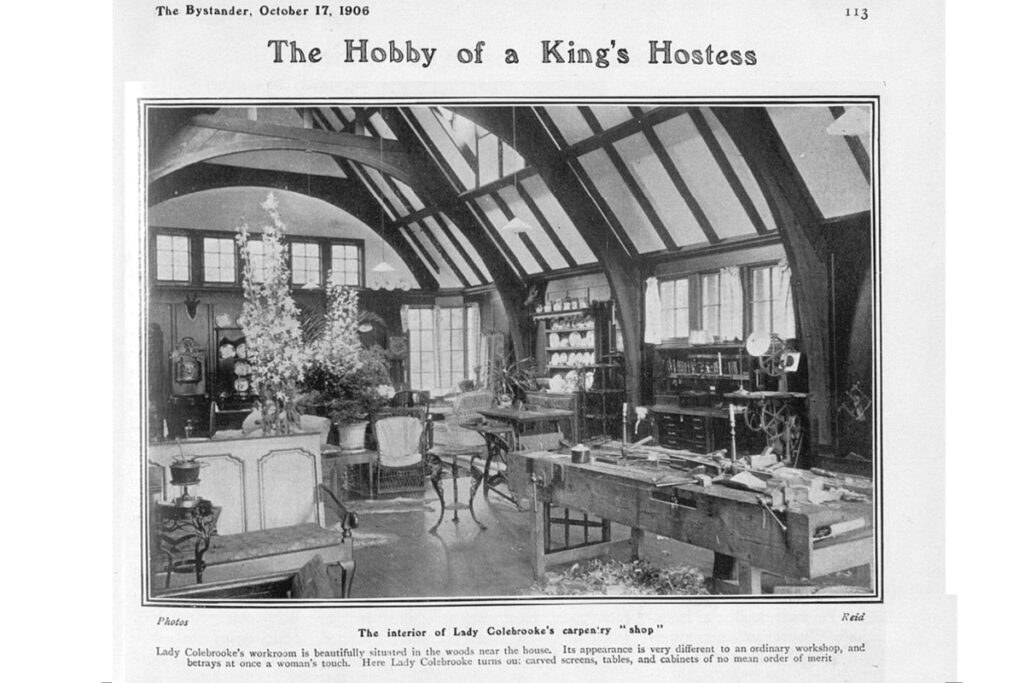

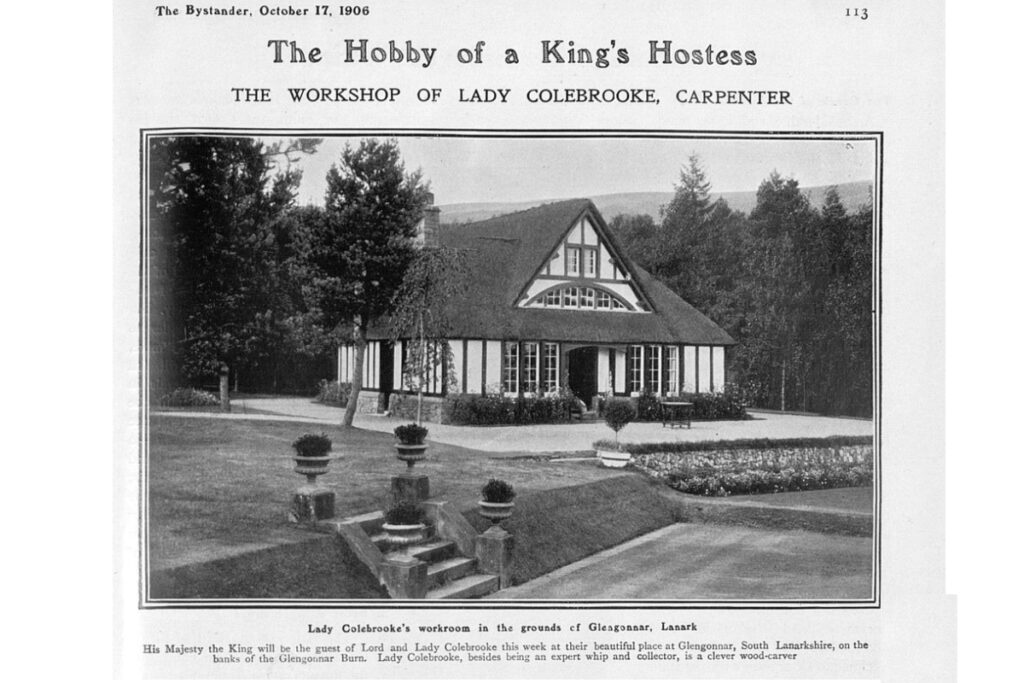

Lady Colebrooke’s Workshop was perhaps the most notable feature of Glengonnar House. Set beyond the lawns, some distance to the house, it was a fanciful construction said to represent an old English farmhouse but – rather incongruously – thatched in heather. The oak frame was exposed within the lofty interior which accommodated both woodworking machinery and all the appurtenances required for a dainty tea party. Photographs show an electric-driven bandsaw and table saw; equipment for steaming timber, and various tool racks and work benches, all set between floral arrangements, potted palms, and comfortable soft furnishings. During autumn months, Lady Colebrooke would build furniture in her workshop while Sir Edward was on the grouse moor, and she sometimes ran carpentry and craft classes for the women and girls of the estate, continuing a Colebrooke tradition. The workshop or “heather house” was also a boon when it came to entertaining, and during grand garden parties a tented passage could be set up across the lawn to link the workshop with the house.

King Edward VII spent four nights at Glengonnar in October 1906 and arrangements for this grand visit were probably already being planned in February of that year when the King conferred a peerage on Sir Edward. The now Lord and Lady Colebrooke were lavish hosts, and despite winter weather the Royal visit proved a great success.

Following this triumph, the Colebrookes spent little time at Glengonnar, and many have concluded that the extravagant expenditure on the Royal visit brought Lord Colebrook close to bankruptcy. By the end of 1907 they had sold their prestigious London house and moved into a small house on the Royal estate at Windsor Park. The King also made a building available for Lady Colebrooke to use as a sculpture studio.

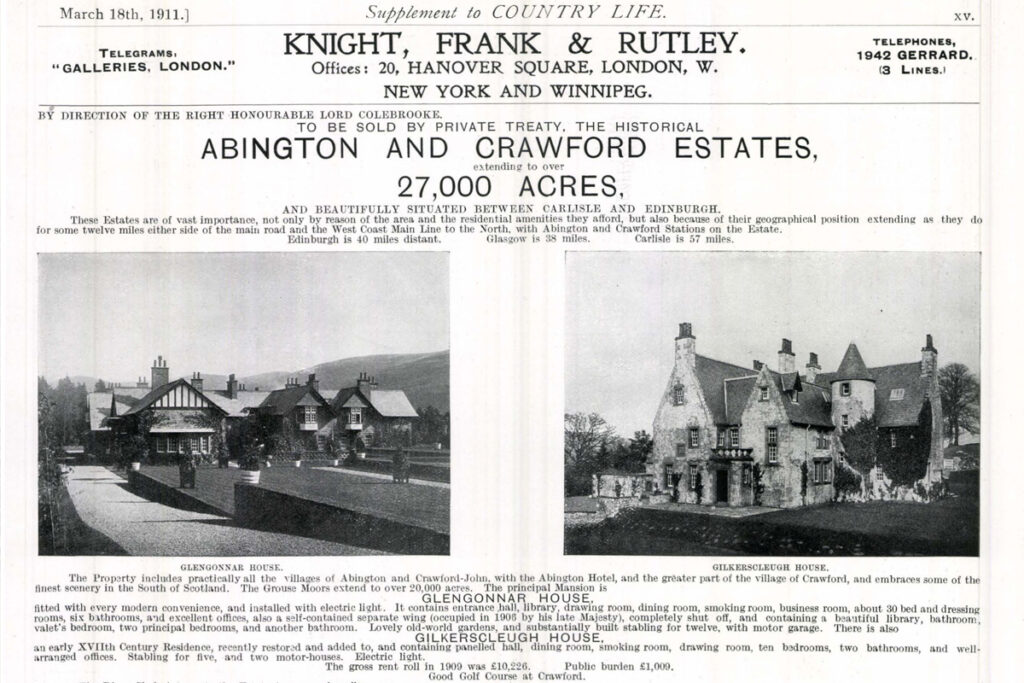

Glengonnar, and the entire 30,000 acre Abington estate, was put up for sale in 1910 and again in 1911, and 1913, but found now buyers. Times were changing, and the age of the great estates was drawing to an end. It was suggested that the sale of the estate might have been anticipated prior to the King’s visit, as the title “Baron Colebrooke of Stebunheath” (a parish in Middlesex) was adopted rather than the expected Baron Colebrooke of Abington.

The Colebrookes maintained their place in London society. Lord Colebrooke remained close to the Royal family, serving as a lord in waiting to George V following the death of his father Edward VII in 1910. During World War One, Lady Colebrooke was one of a group of society ladies who signed up to work in munitions factories, working and living alongside working women for six months in order to support and encourage the war effort. Lady Colebrooke’s practical skills equipped her to tackle more skilled roles than fellow socialites (and earn a higher wage !). Later in the war she took a similar much-publicised role as an assistant in a New York department store to encourage the women of the USA to do their bit for the war effort.

In 1921 Guy, their only son and heir, died at an age of 27, and consequently the hard-earned baroncy was extinguished on the death of Lord Colebrooke. Following the first war, the Colebrooke’s spent much of their time in the fashionable watering holes in the south of France and north of Italy. Lady Colebrooke earned a living as a professional sculptor and later ran a “funny little shop” in Paris (which was opened by Dame Nellie Melba), where she sold her decorative paintings on glass. She died in Cannes, aged in 1944

Lord Colebrooke’s trustees put the Abington estate on the market again in 1921, and sought to rent out Glengonnar for the shooting season, or for longer periods. The Countess of Stafford, presumably while renting Glengonnar, held a garden party for local WRI in the “heather house” during 1920, perhaps marking a last hurrah for Glengonnar. Various contents were sold in 1923 and by the mid 30’s, both Glengonnar House and the workshop were listed as empty in valuation roles.

In 1939 a camp of 13 wooden huts was set among the woods close to the former site of Abington House. Known as Glengonnar Camp, it was designed to accommodate children evacuated from London, but ultimately housed children displaced by the war in Europe. It’s been said that Glengonnar House was used in association with the camp, but we’ve come across nothing in available documents to support this; any insight into the history of the house over WW2 would be very welcome. The house was certainly demolished by 1947 when contractors advertised the sale of doors, panelling, and other components from Glengonnar and other country houses.

Robin Chesters 25th January 2025

Unless otherwise stated, all text, images, and other media content are protected under copyright. If you wish to share any content featured on Clydesdale's Heritage, please get in touch to request permission.